For an embodiment of the word singlehanded you might turn to the heroine of the recent movie Woman at War. It’s about an Icelandic eco-saboteur who blows up rural power lines and hides in scenic spots from helicopters hunting her and is pretty good with a bow and arrow. But the most famous and effective eco-sabotage in the island’s history was not singlehanded.

In a farming valley on the Laxa River in northern Iceland in August 25, 1970, community members blew up a dam to protect farmland from being flooded. After the dam was dynamited, more than a hundred farmers claimed credit (or responsibility). There were no arrests, and there was no dam, and there were some very positive consequences, including protection of the immediate region and new Icelandic environmental regulations and awareness. It’s almost the only story I know of environmental sabotage having a significant impact, and it may be because it expressed the will of the many, not the few.

We are not very good at telling stories about a hundred people doing things or considering that the qualities that matter in saving a valley or changing the world are mostly not physical courage and violent clashes but the ability to coordinate and inspire and connect with lots of other people and create stories about what could be and how we get there. Back in 1970, the farmers did produce a nice explosion, and movies love explosions almost as much as car chases, but it came at the end of what must have been a lot of meetings, and movies hate meetings.

Halla, the middle-aged protagonist of Woman at War is also a choir director, and being good at getting a group to sing in harmony has more to do with how most environmental battles are actually won than her solo exertions. The movie—which keeps lingering without irony on pictures in her Reykjavik flat of negotiations-and-meetings endurance champions Gandhi and Mandela—doesn’t seem to know it, but it also doesn’t seem to care about how you do this thing that saves rivers or islands or the earth.

Positive social change results mostly from connecting more deeply to the people around you than rising above them, from coordinated rather than solo action. Among the virtues that matter are those traditionally considered feminine rather than masculine, more nerd than jock: listening, respect, patience, negotiation, strategic planning, storytelling. But we like our lone and exceptional heroes, and the drama of violence and virtue of muscle, or at least that’s what we get, over and over, and in the course of getting them we don’t get much of a picture of how change happens and what our role in it might be, or how ordinary people matter. “Unhappy the land that needs heroes” is a line of Bertold Brecht’s I’ve gone to dozens of times, but now I’m more inclined to think, pity the land that thinks it needs a hero, or doesn’t know it has lots and what they look like.

In the wake of Robert Mueller’s long-awaited report, a lot of people reminded us that counting on Mueller to be the St. George who slew our dirtbag dragon was a way of writing off our own obligation and capacity.

Woman at War veers off into another plotline, because after all a woman is at the center, and, conventionally, women who do anything impersonal must be conflicted. Like most movies, it’s more interested in personal stuff, or suggests that we do other stuff for purely personal reasons, so the question of what the hell you do about planetary destruction just sort of fades away. It’s kind of like The Hunger Games, whose author could imagine violently overthrowing an old order—and archer Katniss Everdeen is supremely good at violence—but not creating a new one that’s different, or doing anything political with a larger group that’s not corrupt and hardly worth the bother. Thus, at the drab end of The Hunger Games, Everdeen goes off and has babies with her man in a horribly rugged-individualist Little House on the Prairie nuclear-family in the nuclear-ruins way, or if you prefer, a Voltairian We Must All Tend Our Gardens way if that’s what Voltaire meant at the end of Candide. The archer protagonist of Woman at War also dwindles down to the domestic in the end.

I’m interested in impersonal stuff too, or convinced that this other stuff that’s supposed to be impersonal feeds hearts and souls and is also about love and our deepest needs, because what’s deep is also broad. We need hope and purpose and membership in a community beyond the nuclear family. And this connection is both personally fulfilling and how we get stuff done that needs to be done. Lone hero narratives push one figure into the public eye, but they push everyone else back into private life, or at least passive life.

The legal expert and writer Dahlia Lithwick told me that when she was gearing up to write about the women lawyers who have fought and defeated the Trump Administration in civil rights case after case over the past couple of years, various people insisted she should write a book about Ruth Bader Ginsburg instead. There are already books and films (and t-shirts and coffee mugs galore) about Ginsburg, and these were requests to narrow the focus down to one well-known superstar, when Dahlia in her forthcoming book is trying to broaden it to take in underrecognized constellations of other women lawyers.

Which is to say that the problem of the singlehanded hero exists in nonfiction and news and even history (where it was dubbed the Great Man Theory of History) as much as it does in fiction and film. (There’s also a Terrible Man Theory of History that, for example, in focusing on Trump excuses and ignores the longer history of right-wing destruction and delusion.) To concentrate on Ginsburg is to suggest that one transcendently exceptional individual at the apex of power is who matters. To look at these other lawyers is to suggest that power is dispersed and decisions in various courts across the land matter and so do the lawyers who win them and the people who support them.

This idea that our fate is handed down to us from above is built into so many stories. Even Supreme Court rulings around marriage equality or abortion often reflect shifts in values in the broader society as well as the elections that determine who sits on the court. Those broad shifts are made by the many in acts that often go unrecognized. Even if you only cherish personal life, you have to recognize the public struggles that impact who gets to get married, who gets a living wage and healthcare and education and housing and clean drinking water. Also if you’re one of the 82 people who burned to death in the Paradise fire last year, the consequences of public policy were very personal.

This idea that our fate is handed down to us from above is built into so many stories.

We like heroes and stars and their opposites, though I’m not sure who I mean by we, except maybe the people in charge of too many of our stories, who are themselves often elites who believe devoutly in elites, which is what heroes and stars are often presumed to be. There’s a scorching song by Liz Phair I think about whenever I think about heroes. She sang:

He’s just a hero in a long line of heroes

Looking for something attractive to save

They say he rode in on the back of a pick-up

And he won’t leave town till you remember his name

It’s a caustic revision of the hero as an attention-getter, a party-crasher, a fame-seeker, and at least implicitly a troublemaker in the guise of a problem-solver. And maybe we as a society are getting tired of heroes, and a lot of us are certainly getting tired of overconfident white men. Even the idea that the solution will be singular and dramatic and in the hands of one person erases that the solutions to problems are often complex and many faceted and arrived at via negotiations. The solution to climate change is planting trees but also transitioning (rapidly) away from fossil fuels but also energy efficiency and significant design changes but also a dozen more things about soil and agriculture and transportation and how systems work. There is no solution, but there are are many pieces that add up to a solution, or rather to a modulation of the problem of climate change.

Phair is not the first woman to be caustic about heroes. Ursula K. Le Guin writes,

When she was planning the book that ended up as Three Guineas, Virginia Woolf wrote a heading in her notebook, “Glossary”; she had thought of reinventing English according to a new plan, in order to tell a different story. One of the entries in this glossary is heroism, defined as “botulism.” And hero, in Woolf’s dictionary, is “bottle.” The hero as bottle, a stringent reevaluation. I now propose the bottle as hero.

That’s from Le Guin’s famous 1986 essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” which notes that though most of early human food was gathered, and gathering was often women’s work, it’s hunting that made for dramatic stories. And she argues that though the earliest tools have often been thought to be weapons in all their sharp-and-pointy deadliness, containers—thus her bottle joke—were maybe earlier and as or more important, gender/genital implications intended. Hunting is full of singular drama—with my spear I slayed this bear. A group of women gathering grain, on the other hand, doesn’t have a singular gesture or target or much drama. “I said it was hard to make a gripping tale of how we wrested the wild oats from their husks, I didn’t say it was impossible,” says Le Guin toward the end of her essay. Among the Iban people of Borneo, I read recently, the men gained status by headhunting, the women by weaving. Headhunting is more dramatic, but weaving is itself a model for storytelling’s integration of parts and materials into a new whole.

Speaking of women, there’s a new drug for postpartum depression (PPD) about which some experts pointed out that “mothers and advocates alike should consider if the drug is a BandAid on the larger wound of America’s treatment of mothers. How would PPD rates be affected if we adopted policies that support parents, like subsidized child care, paid parental leave, and health care norms that center mothers’ choices in childbirth and the postpartum period? Pegging the complexities of a new mother’s adjustment as a mental illness ignores cultural factors that cause new parents to feel unsupported.” That is, maybe we need a thousand acts of kindness and connection, rather than deus ex machina drugs to mute the pain of their absence.

That’s another part of our rugged individualism and hero culture, the idea that all problems are personal and they’re all soluble by personal responsibility—or medication that helps you accept what you cannot change, when it can be changed but not by you personally. It’s a framework that eliminates the possibility of deeper, broader change or of holding accountable the powerful who create and benefit from the status quo and its myriad forms of harm. The narrative of individual responsibility and change protects stasis, whether it’s adapting to inequality or poverty or pollution.

Our largest problems won’t be solved by heroes. They’ll be solved, if they are, by movements, coalitions, civil society. The climate movement, for example, has been first of all a mass effort, and if figures like Bill McKibben stand out—well he stands out as the cofounder of a global climate action group whose network is in 188 countries and the guy who keeps saying versions of “The most effective thing you can do about climate as an individual is stop being an individual.” And he’s often spoken of a book that influenced him early on, The Pushcart War, a 1964 children’s tale about pushcart vendors organizing to protect their own in a territorial war against truck drivers on the streets of New York. And, plot spoiler, winning.

I was thinking about all this when I was thinking about Sweden’s Greta Thunberg, a truly remarkable young woman, someone who has catalyzed climate action across the world. But the focus on her may obscure that many remarkable young people before her have stood up and spoken passionately about climate change. Her words mattered because we responded, and we responded in part because the media elevated her as they had not elevated her predecessors, and they elevated her because somehow climate change has been taken more seriously, climate action has acquired momentum, probably due to the actions of tens of thousands or millions who will not be credited with this change. She began alone, but publicly, not secretly, and that made it possible for her actions to be multiplied by more and more others.

The narrative of individual responsibility and change protects stasis, whether it’s adapting to inequality or poverty or pollution.

She’s been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, which is sometimes awarded to groups and teams, but awards also tend to single out individuals. Some people use their acceptance speech to try to reverse the hero myth and thank all the people who were with them or describe themselves as members of a tribe or an alliance or a movement. Ada Limon, accepting the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry a few weeks ago, said “We write with all the good ghosts in our corners. I, for one, have never made anything alone, never written a single poem alone” and then listed a lot of people who helped or who mattered or who didn’t get to write poetry.

A general is not much without an army, and social change is not even modeled on generals and armies, because the outstanding figures get others to act willingly, not by command. We would do well to call them catalysts rather than leaders. Martin Luther King was not the Civil Rights Movement and Cesar Chavez was not the farmworker rights movement and to mistake them for that denies the multitudes the recognition they deserve but more importantly denies us strategic understandings when we need them most. Which begins with our own power and ends with how change works.

In the wake of Robert Mueller’s long-awaited report, a lot of people reminded us that counting on Mueller to be the St. George who slew our dirtbag dragon was a way of writing off our own obligation and capacity. Lithwick said it best a month before the investigation wrapped up: “The prevailing ethos seems to be that so long as there is somebody else out there who is capable of Doing Something, the rest of us are free to desist. And for the most part, the person deemed to be Doing Something is Robert Mueller.” Leaders beget followers, and followers are people who’ve surrendered some of their capacities to think and to act. Unfortunate the land whose citizens pass the buck to a hero.

The standard action movie narrative require one exceptional person in the foreground, which requires the rest of the characters to be on the spectrum from useless to clueless to wicked, plus a few moderately helpful auxiliary characters. There are not a lot of movies about magnificent collective action, something I noticed when I wrote about what actually happens in sudden catastrophes—fires, floods, heat waves, freak storms, the kind of calamity that we will see more and more as the age of climate change takes hold. Disaster movies begin with a sudden upset in the order of things—the tower becomes a towering inferno, the meteor heads toward earth, the earth shakes—and then smooths it all over with a kind of father-knows-best here-comes-a-hero plotline of rescuing helpless women and subduing vicious men. Patriarchal authority itself is shown as the solution to disasters, or a sort of drug to make us feel secure despite them.

One of the joys of Liz Phair’s song is that she lets us recognize heroism as a disaster itself. I found out in the research for what became my 2009 book A Paradise Built in Hell, that institutional authorities often behave badly in disasters, in part because they assume that the rest of us will behave badly in the power vacuum disasters bring on and thus they too often turn humanitarian relief into aggressive policing, often in protection of property and the status quo rather than disaster victims. But ordinary people generally behave magnificently, taking care of each other and improvising rescues and the conditions of survival, connecting with each other in ways they might not in everyday life and sometimes finding in that connection something so valuable and meaningful that their stories about who they were and met and what they did shine with joy.

That is, I found in disasters a window onto what so many of us really want and don’t get, a need we hardly name or recognize. There are not a lot of movies that can even imagine this profound emotion I think of as public love, this sense of meaning, purpose, power, belonging to a community, a society, a city, a movement. I’ve talked to survivors of 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, read stories of earlier disasters, blitzes, and found that emotion swimming up through the wreckage and found that people are ravenous for it.

William James said of the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, “Surely the cutting edge of all our usual misfortunes comes from their character of loneliness.” That is, if I lose my home, I’m cast out among those who remain comfortable, but if we all lose our homes in the earthquake, we’re in this together. One of my favorite sentences from a 1906 survivor is this: “Then when the dynamite explosions were making the night noisy and keeping everybody awake and anxious, the girls or some of the refugees would start playing the piano, and Billy Delaney and other folks would start singing; so that the place became quite homey and sociable, considering it was on the sidewalk, outside the high school, and the town all around it was on fire.”

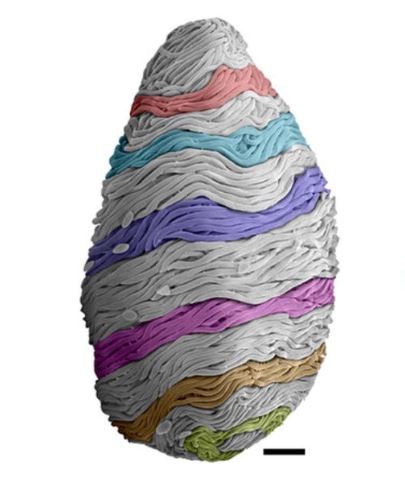

I don’t know what Billy Delaney or the girls sang, or what stories the oat gatherers Le Guin writes about might have told. But I do have a metaphor, which is itself a kind of carrier bag and metaphor literally means to carry something beyond, carrying being the basic thing language does, language being great nets we weave to hold meaning. Jonathan Jones, an indigenous Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi Australian artist, has an installation—a great infinity-loop figure eight of feathered objects on a curving wall in the Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane that mimics a murmuration, one of those great flocks of birds in flight that seems to swell and contract and shift as the myriad individual creatures climb and bank and turn together, not crashing into each other, not drifting apart.

From a distance Jones’s objects look like birds; up close they are traditional tools of stick and stone with feathers attached, tools of making taking flight. The feathers were given to him by hundreds who responded to the call he put out, a murmuration of gatherers. “I’m interested in this idea of collective thinking,” he told a journalist. “How the formation of really beautiful patterns and arrangements in the sky can help us potentially start to understand how we exist in this country, how we operate together, how we can all call ourselves Australians. That we all have our own little ideas which can somehow come together to make something bigger.”

What are human murmurations, I wondered? They are, speaking of choruses, in Horton Hears a Who, the tiny Whos of Whoville, who find that if every last one of them raises their voice, they become loud enough to save their home. They are a million and a half young people across the globe on March 15 protesting climate change, coalitions led by Native people holding back fossil fuel pipelines across Canada, the lawyers and others who converged on airports all over the US on January 29, 2017, to protest the Muslim ban.

They are the hundreds who turned out in Victoria, BC, to protect a mosque there during Friday prayers the week after the shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand. My cousin Jessica was one of them, and she wrote about how deeply moving it was for her, “At the end, when prayers were over, and the mosque was emptying onto the street, if felt like a wedding, a celebration of love and joy. We all shook hands and hugged and spoke kindly to each other—Muslim, Jew, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist, atheist…” We don’t have enough art to make us see and prize these human murmurations even when they are all around us, even when they are doing the most important work on earth.

In 2017, the Aussie psych-rock mob King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard pulled off something incredible. At the beginning of the year, they promised that they'd release five new albums before the year was over. And then they did it. And all the albums were worth hearing. (For my money, the best of them was …

In 2017, the Aussie psych-rock mob King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard pulled off something incredible. At the beginning of the year, they promised that they'd release five new albums before the year was over. And then they did it. And all the albums were worth hearing. (For my money, the best of them was …  Ariana Grande fucked up. The pop star just got a tattoo to celebrate her new #1 single "

Ariana Grande fucked up. The pop star just got a tattoo to celebrate her new #1 single "