ChatGPT is being heralded as a revolution in ‘artificial intelligence’ (AI) and has been taking the media and tech world by storm since launching in late 2022.

According to OpenAI, ChatGPT is “an artificial intelligence trained to assist with a variety of tasks.” More specifically, it is a large language model (LLM) designed to produce human-like text and converse with people, hence the “Chat” in ChatGPT.

GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer. The GPT models are pre-trained by human developers and then are left to learn for themselves and generate ever increasing amounts of knowledge, delivering that knowledge in an acceptable way to humans (chat).

Practically, this means you present the model with a query or request by entering it into a text box. The AI then processes this request and responds based on the information that it has available. It can do many tasks, from holding a conversation to writing an entire exam paper; from making a brand logo to composing music and more. So much more than a simple Google-type search engine or Wikipedia, it is claimed.

Human developers are working to raise the ‘intelligence’ of GPTs. The current version of GPT is 3.5 with 4.0 coming out by the end of this year. And it is rumoured that ChatGPT-5 could achieve ‘artificial general intelligence’ (AGI). This means it could pass the Turing test, which is a test that determines if a computer can communicate in a manner that is indistinguishable from a human.

Will LLMs be a game changer for capitalism in this decade? Will these self-learning machines be able to increase the productivity of labour at an unprecedented rate and so take the major economies out of their current ‘long depression’ of low real GDP, investment and income growth; and then enable the world to take new strides out of poverty? This is the claim by some of the ‘techno-optimists’ that occupy the media.

Let’s consider the answers to those questions.

First, just how good and accurate are the current versions of ChatGPT? Well, not very, just yet. There are plenty of “facts” about the world which humans disagree on. Regular search lets you compare those versions and consider their sources. A language model might instead attempt to calculate some kind of average of every opinion it’s been trained on—which is sometimes what you want, but often is not. ChatGPT sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers. Let me give you some examples.

I asked ChatGPT 3.5: who is Michael Roberts, Marxist economist? This was the reply.

This is mostly right but it is also wrong in parts (I won’t say which).

Then I asked it to review my book, The Long Depression. This is what it said:

This gives a very ‘general’ review or synopsis of my book, but leaves out the kernel of the book’s thesis: the role of profitability in crises under capitalism. Why, I don’t know.

So I asked this question about Marx’s law of profitability:

Again, this is broadly right – but just broadly. The answer does not really take you very far in understanding the law. Indeed, it is no better than Wikipedia. Of course, you can dig (prompt) further to get more detailed answers. But there seems to be some way to go in replacing human research and analysis.

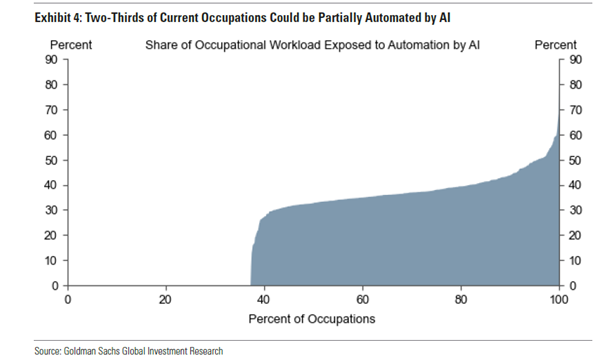

Then there is the question of the productivity of labour and jobs. Goldman Sachs economists reckon that if the technology lived up to its promise, it would bring “significant disruption” to the labour market, exposing the equivalent of 300m full-time workers across the major economies to automation of their jobs. Lawyers and administrative staff would be among those at greatest risk of becoming redundant (and probably economists). They calculate that roughly two-thirds of jobs in the US and Europe are exposed to some degree of AI automation, based on data on the tasks typically performed in thousands of occupations.

Most people would see less than half of their workload automated and would probably continue in their jobs, with some of their time freed up for more productive activities. In the US, this would apply to 63% of the workforce, they calculated. A further 30% working in physical or outdoor jobs would be unaffected, although their work might be susceptible to other forms of automation.

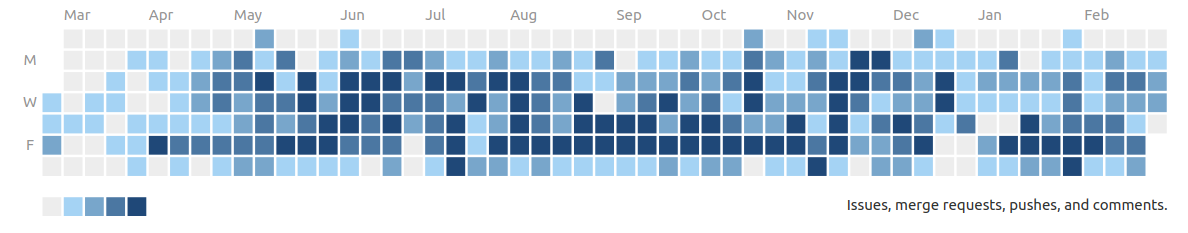

The GS economists concluded: “Our findings reveal that around 80% of the US workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of workers may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted.”

With access to an LLM, about 15% of all worker tasks in the US could be completed significantly faster at the same level of quality. When incorporating software and tooling built on top of LLMs, this share increases to 47-56% of all tasks. About 7% of US workers are in jobs where at least half of their tasks could be done by generative AI and are vulnerable to replacement. At a global level, since manual jobs are a bigger share of employment in the developing world, GS estimates about a fifth of work could be done by AI — or about 300m full-time jobs across big economies.

These job loss forecasts are nothing new. In previous posts, I have outlined several forecasts on the number of jobs that will be lost to robots and AI over the next decade or more. It appears to be huge; and not just in manual work in factories but also in so-called white-collar work.

It is in the essence of capitalist accumulation that the workers will continually face the loss of their work from capitalist investment in machines. The replacement of human labour by machines started at the beginning of the British Industrial Revolution in the textile industry, and automation played a major role in American industrialization during the 19th century. The rapid mechanization of agriculture starting in the middle of the 19th century is another example of automation.

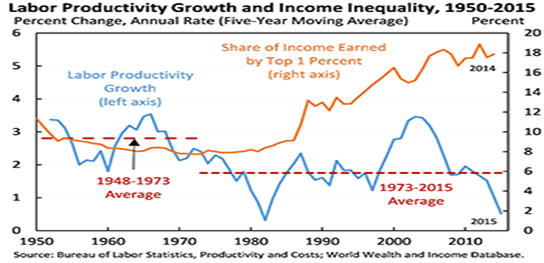

As Engels explained, whereas mechanisation not only shed jobs, often it also created new jobs in new sectors, as Engels noted in his book, The condition of the working class in England (1844) – see my book on Engels’ economics pp54-57. But as Marx identified this in the 1850s: “The real facts, which are travestied by the optimism of the economists, are these: the workers, when driven out of the workshop by the machinery, are thrown onto the labour-market. Their presence in the labour-market increases the number of labour-powers which are at the disposal of capitalist exploitation…the effect of machinery, which has been represented as a compensation for the working class, is, on the contrary, a most frightful scourge. …. As soon as machinery has set free a part of the workers employed in a given branch of industry, the reserve men are also diverted into new channels of employment and become absorbed in other branches; meanwhile the original victims, during the period of transition, for the most part starve and perish.” Grundrisse. The implication here is that automation means increased precarious jobs and rising inequality.

Up to now, mechanisation has still required human labour to start and maintain it. But are we now moving towards the takeover of all tasks, and especially those requiring complexity and ideas with LLMs? And will this mean a dramatic rise in the productivity of labour so that capitalism will have a new lease of life?

If LLMs can replace human labour and thus raise the rate of surplus value dramatically, but without a sharp rise in investment costs of physical machinery (what Marx called a rising organic composition of capital), then perhaps the average profitability of capital will jump back from its current lows.

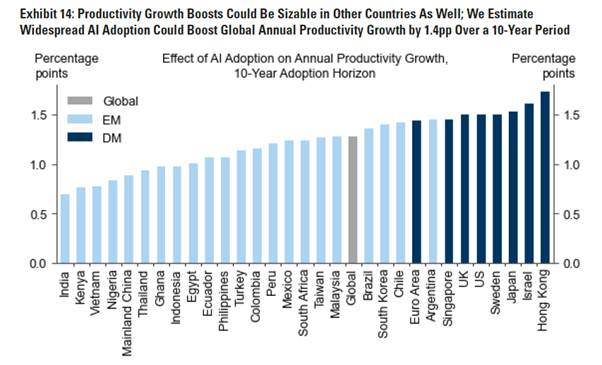

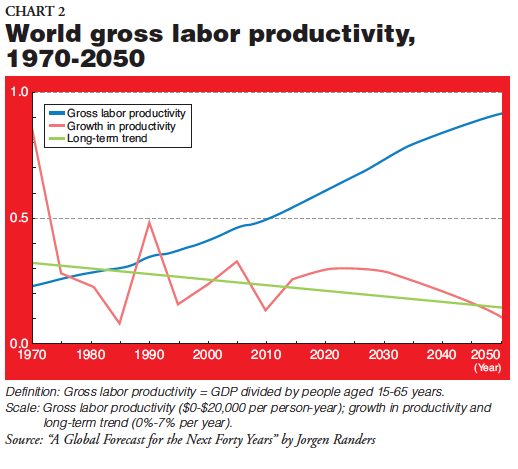

Goldman Sachs claims that these “generative” AI systems such as ChatGPT could spark a productivity boom that would eventually raise annual global GDP by 7% over a decade. If corporate investment in AI continued to grow at a similar pace to software investment in the 1990s, US AI investment alone could approach 1% of US GDP by 2030.

I won’t go into how GS calculates these outcomes, because the results are conjectures. But even if we accept the results, are they such an exponential leap? According to the latest forecasts by the World Bank, global growth is set to decline by roughly a third from the rate that prevailed in the first decade of this century—to just 2.2% a year. And the IMF puts the average growth rate at 3% a year for the rest of this decade.

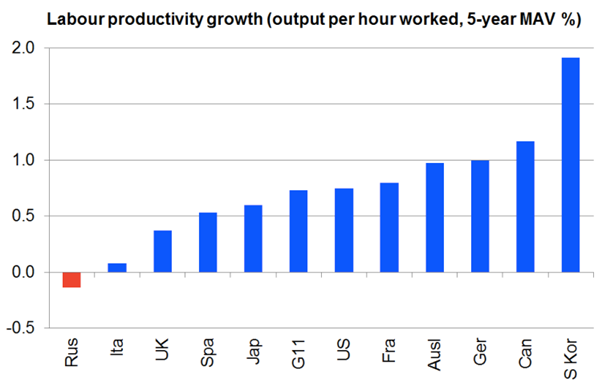

If we add in the GS forecast of the impact of LLMs, we get about 3.0-3.5% a year for global real GDP growth, maybe – and this does not account for population growth. In other words, the likely impact would be no better than the average seen since the 1990s. That reminds us of what Economist Robert Solow famously said in 1987 that the “computer age was everywhere except for the productivity statistics.”

US economist Daren Acemoglu adds that not all automation technologies actually raise the productivity of labour. That’s because companies mainly introduce automation in areas that may boost profitability, like marketing, accounting or fossil fuel technology, but not raise productivity for the economy as a whole or meet social needs. Big Tech has a particular approach to business and technology that is centered on the use of algorithms for replacing humans. It is no coincidence that companies such as Google are employing less than one tenth of the number of workers that large businesses, such as General Motors, used to do in the past. This is a consequence of Big Tech’s business model, which is based not on creating jobs but automating them.

That’s the business model for AI under capitalism. But under cooperative commonly owned automated means of production, there are many applications of AI that instead could augment human capabilities and create new tasks in education, health care, and even in manufacturing. Acemoglu suggested that “rather than using AI for automated grading, homework help, and increasingly for substitution of algorithms for teachers, we can invest in using AI for developing more individualized, student-centric teaching methods that are calibrated to the specific strengths and weaknesses of different groups of pupils. Such technologies would lead to the employment of more teachers, as well as increasing the demand for new teacher skills — thus exactly going in the direction of creating new jobs centered on new tasks.” And rather than reduce jobs and the livelihoods of humans, AI under common ownership and planning could reduce the hours of human labour for all.

And then there is the issue of the profitability boost provided by AI technology. Even if LLM investment requires less physical means of production and lowers costs of such capital, the loss of human labour power could be even greater. So Marx’s law of profitability would still apply. It’s the great contradiction of capitalism that increasing the productivity of labour through more machines (AI) reduces the profitability of capital. That leads to regular and recurring crises of production, investment and employment – of increasing intensity and duration.

Finally, there is the question of intelligence. Microsoft argues that intelligence is a “very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience.” Microsoft hints that LLMs could soon obtain this ‘generalised intelligence’ and surpass all human ability to think.

But even here, there is scepticism. “The ChatGPT model is huge, but it’s not huge enough to retain every exact fact it’s encountered in its training set. It can produce a convincing answer to anything, but that doesn’t mean it’s reflecting actual facts in its answers. You always have to stay sceptical and fact check what it tells you. Language models are also famous for “hallucinating”—for inventing new facts that fit the sentence structure despite having no basis in the underlying data.” That’s not very encouraging.

But Guglielmo Carchedi has a more fundamental reason to deny that AI can replace human ‘intelligence’. Carchedi and Roberts: “machines behave according only to the rules of formal logic. Contrary to humans, machines are structurally unable to behave according to the rules of dialectical thinking. Only humans do that.” (Capitalism in the 21st century, p167). Here is the ChatGPT answer to the dialectical question: “Can A be equal to A and at the same time be different from A?” “No, it is not possible for A to be equal to A and at the same time be different from A. This would be a contradiction in terms, as the statement “A is equal to A” is a tautology and always true, while the statement “A is different from A” is a contradiction and always false. Therefore, these two statements cannot both be true at the same time.”

Machines cannot think of potential and qualitative changes. New knowledge comes from such transformations (human), not from the extension of existing knowledge (machines). Only human intelligence is social and can see the potential for change, in particular social change, that leads to a better life for humanity and nature.

The Pentagon doesn't meme like you or I. Before the DoD's cyber warriors can shitpost, images must be approved, tweets drafted and redrafted, and everything has to go through the chain of command.

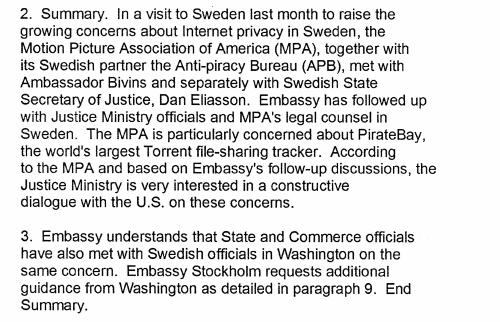

The Pentagon doesn't meme like you or I. Before the DoD's cyber warriors can shitpost, images must be approved, tweets drafted and redrafted, and everything has to go through the chain of command. Over the past several years, copyright holders have asked Google to remove billions of links to allegedly pirated content.

Over the past several years, copyright holders have asked Google to remove billions of links to allegedly pirated content.

There are a handful of traditions we have at TorrentFreak, and remembering the first raid on The Pirate Bay is one of them.

There are a handful of traditions we have at TorrentFreak, and remembering the first raid on The Pirate Bay is one of them.