My life philosophy.

Who needs religion when you have Bill & Ted?

Today at the Chaos Computer Congress (30C3), xobs and I disclosed a finding that some SD cards contain vulnerabilities that allow arbitrary code execution — on the memory card itself. On the dark side, code execution on the memory card enables a class of MITM (man-in-the-middle) attacks, where the card seems to be behaving one way, but in fact it does something else. On the light side, it also enables the possibility for hardware enthusiasts to gain access to a very cheap and ubiquitous source of microcontrollers.

In order to explain the hack, it’s necessary to understand the structure of an SD card. The information here applies to the whole family of “managed flash” devices, including microSD, SD, MMC as well as the eMMC and iNAND devices typically soldered onto the mainboards of smartphones and used to store the OS and other private user data. We also note that similar classes of vulnerabilities exist in related devices, such as USB flash drives and SSDs.

Flash memory is really cheap. So cheap, in fact, that it’s too good to be true. In reality, all flash memory is riddled with defects — without exception. The illusion of a contiguous, reliable storage media is crafted through sophisticated error correction and bad block management functions. This is the result of a constant arms race between the engineers and mother nature; with every fabrication process shrink, memory becomes cheaper but more unreliable. Likewise, with every generation, the engineers come up with more sophisticated and complicated algorithms to compensate for mother nature’s propensity for entropy and randomness at the atomic scale.

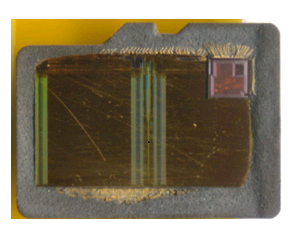

These algorithms are too complicated and too device-specific to be run at the application or OS level, and so it turns out that every flash memory disk ships with a reasonably powerful microcontroller to run a custom set of disk abstraction algorithms. Even the diminutive microSD card contains not one, but at least two chips — a controller, and at least one flash chip (high density cards will stack multiple flash die). You can see some die shots of the inside of microSD cards at a microSD teardown I did a couple years ago.

In our experience, the quality of the flash chip(s) integrated into memory cards varies widely. It can be anything from high-grade factory-new silicon to material with over 80% bad sectors. Those concerned about e-waste may (or may not) be pleased to know that it’s also common for vendors to use recycled flash chips salvaged from discarded parts. Larger vendors will tend to offer more consistent quality, but even the largest players staunchly reserve the right to mix and match flash chips with different controllers, yet sell the assembly as the same part number — a nightmare if you’re dealing with implementation-specific bugs.

The embedded microcontroller is typically a heavily modified 8051 or ARM CPU. In modern implementations, the microcontroller will approach 100 MHz performance levels, and also have several hardware accelerators on-die. Amazingly, the cost of adding these controllers to the device is probably on the order of $0.15-$0.30, particularly for companies that can fab both the flash memory and the controllers within the same business unit. It’s probably cheaper to add these microcontrollers than to thoroughly test and characterize each flash memory chip, which explains why managed flash devices can be cheaper per bit than raw flash chips, despite the inclusion of a microcontroller.

The downside of all this complexity is that there can be bugs in the hardware abstraction layer, especially since every flash implementation has unique algorithmic requirements, leading to an explosion in the number of hardware abstraction layers that a microcontroller has to potentially handle. The inevitable firmware bugs are now a reality of the flash memory business, and as a result it’s not feasible, particularly for third party controllers, to indelibly burn a static body of code into on-chip ROM.

The crux is that a firmware loading and update mechanism is virtually mandatory, especially for third-party controllers. End users are rarely exposed to this process, since it all happens in the factory, but this doesn’t make the mechanism any less real. In my explorations of the electronics markets in China, I’ve seen shop keepers burning firmware on cards that “expand” the capacity of the card — in other words, they load a firmware that reports the capacity of a card is much larger than the actual available storage. The fact that this is possible at the point of sale means that most likely, the update mechanism is not secured.

In our talk at 30C3, we report our findings exploring a particular microcontroller brand, namely, Appotech and its AX211 and AX215 offerings. We discover a simple “knock” sequence transmitted over manufacturer-reserved commands (namely, CMD63 followed by ‘A’,'P’,'P’,'O’) that drop the controller into a firmware loading mode. At this point, the card will accept the next 512 bytes and run it as code.

From this beachhead, we were able to reverse engineer (via a combination of code analysis and fuzzing) most of the 8051′s function specific registers, enabling us to develop novel applications for the controller, without any access to the manufacturer’s proprietary documentation. Most of this work was done using our open source hardware platform, Novena, and a set of custom flex circuit adapter cards (which, tangentially, lead toward the development of flexible circuit stickers aka chibitronics).

Significantly, the SD command processing is done via a set of interrupt-driven call backs processed by the microcontroller. These callbacks are an ideal location to implement an MITM attack.

It’s as of yet unclear how many other manufacturers leave their firmware updating sequences unsecured. Appotech is a relatively minor player in the SD controller world; there’s a handful of companies that you’ve probably never heard of that produce SD controllers, including Alcor Micro, Skymedi, Phison, SMI, and of course Sandisk and Samsung. Each of them would have different mechanisms and methods for loading and updating their firmwares. However, it’s been previously noted that at least one Samsung eMMC implementation using an ARM instruction set had a bug which required a firmware updater to be pushed to Android devices, indicating yet another potentially promising venue for further discovery.

From the security perspective, our findings indicate that even though memory cards look inert, they run a body of code that can be modified to perform a class of MITM attacks that could be difficult to detect; there is no standard protocol or method to inspect and attest to the contents of the code running on the memory card’s microcontroller. Those in high-risk, high-sensitivity situations should assume that a “secure-erase” of a card is insufficient to guarantee the complete erasure of sensitive data. Therefore, it’s recommended to dispose of memory cards through total physical destruction (e.g., grind it up with a mortar and pestle).

From the DIY and hacker perspective, our findings indicate a potentially interesting source of cheap and powerful microcontrollers for use in simple projects. An Arduino, with its 8-bit 16 MHz microcontroller, will set you back around $20. A microSD card with several gigabytes of memory and a microcontroller with several times the performance could be purchased for a fraction of the price. While SD cards are admittedly I/O-limited, some clever hacking of the microcontroller in an SD card could make for a very economical and compact data logging solution for I2C or SPI-based sensors.

Slides from our talk at 30C3 can be downloaded here, or you can watch the talk on Youtube below.

Team Kosagi would like to extend a special thanks to .mudge for enabling this research through the Cyber Fast Track program.

Image by Ian Visits in the Londonist Flickr pool and under Creative Commons licence.

Elizabeth Holdsworth takes a look at one of the Science Museum’s most treasured objects.

The Command Module of Apollo 10 basks under spotlights on the ground floor of London’s Science Museum. Nearly 45 years ago this capsule made its way around the moon. It’s now one of the most popular attractions for the museum.

The vessel is the shape of a lampshade (which, we learn, is technically called a frustum). It was equipped with the defences to protect three astronauts from the harshness of space and the fireball of re-entry, yet it is no larger than a very small skip. A very heavy small skip, that is — it weighs nearly seven tons.

This historic little space ship was first loaned to the Science Museum in 1976 from the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, and has remained on an extended loan ever since.

While this object would seem to have little connection to London, other than its longterm residence, the relationship runs deeper. The Apollo 10 Command Module can be seen as one of the city’s most technologically and spiritually important objects; it arguably says more about the achievements of the 20th century than any other single object here.

The Saturn V rockets, which lofted the Apollo capsules to the moon, were developed directly from V2 rocket technology, fired on London by the Nazis only two and a half decades before. One of these V-weapons stands just metres away from the Apollo 10 capsule in the Science Museum.

The astronauts of Apollo 10 never landed on the moon. Their mission, in May 1969, was a dress rehearsal. It was the Apollo 11 mission in July of Aldrin, Armstrong and Collins that one-small-stepped the Apollo program indelibly into public memory. Yet before this could be achieved, the mission of Cernan, Stafford and Young was to make the unimaginably long journey out of Low Earth Orbit and around the moon.

Granted, we know that these astounding events all happened with an urgency spurred on by Cold War fear and international one-upmanship, but the implications for humanity outweighed the bleak political aims of the Space Race. Apollo’s significance for mankind transcended its own ideological atmosphere. On the Apollo missions, for the first time, a human eye could see the planet’s entire orb in a single glance.

In the Apollo 10 Command Module (call-sign Charlie Brown), the three astronauts sailed through space towards the moon. Locked in tow was a Lunar Module designed to make a landing (call-sign Snoopy, it was identical to Aldrin and Armstrong’s lander, Eagle, but never destined to make the giant leap to its full potential), and a Service Module equipped to sustain their lives for the eight-day journey. On completion of the Apollo 10 flight, NASA officials ordered the astronauts of the following mission to adopt more majestic call-signs for their flight vessels, names such as Eagle that would more appropriately represent the seriousness of the moment — perhaps we should say, the gravity — of the first human landing upon the moon.

When Apollo 10 reached the moon Cernan and Stafford test piloted the delicate gold-foil Lunar Module to within a few miles of the surface, then left it empty and adrift. Together the three astronauts sailed around the unseen side of the moon, for a time losing all contact with home. As they rounded the lunar surface they saw the earth rise and they were filled with wonder at the beauty and fragility of the world. The gravitational force of the moon flung them back on their return journey and they silently soared faster than living beings ever traveled before or since.

The detached Command Module now on display in London brought its three occupants blazing back to Earth in a fireball of atmospheric friction. Looking now at the burnished exterior of the craft, its heat shield coating resembles dirty brass or varnished oak, segmented by small triangular windows and studded with rivets. More steam punk than space age.

How different was the view of London in the sixties? St Paul’s Cathedral was still among the tallest buildings on the skyline, God reaching up into the cosmos. It was superseded by the Post Office Tower, a futuristic wand of concrete and glass looming over Fitzrovia. While outer space is infinitely wide and almost empty, in the city, space comes at a premium. And so we built upwards. The Shard is pointing to the sky — the only way is up.

The great city holds more to see and do and more ways to connect and communicate with others than ever before, a caricature of infinity. Yet this vastness can be, for some, a lonely vacuum. As David Bowie sang in his 1969 anthem Space Oddity, capturing for some the spirit of the time: ‘Planet Earth is blue and there’s nothing I can do’. The moon, object of both comforting familiarity and mystical otherness, watches over us and reminds us that on this fragile planet we are together and at home. But the moon is a harsh and lifeless desert. The titles of its great barren seas, Serenity, Tranquility, belie the extreme conditions of scorching airless days and subfreezing nights on a desolate landscape of abrasive, asbestos-like moon dust and rocks far drier than bones.

Now that the technology that got us to the moon lies gathering dust in museums, the most lasting impression we are left with is one of humanity’s self truth. Reflecting on the legacy of the Apollo program, astronaut Eugene Cernan put it perfectly, ‘We went to explore the moon, and in fact discovered the Earth’. But how did one of the most important space ships from that era land in South Kensington?

Objects from the US Space Program were toured during the 1970s both to appeal to the world population’s timely appetite for space travel, but also as a form of victory lap. The Americans had won the race.

Documents from the Science Museum’s archive indicate that the Apollo 10 Command Module had been shown in France and the Netherlands, before coming to London. There is even the suggestion that it spent a brief spell in the Soviet Union. Touring a seven ton space ship, in a state of ‘considerable disrepair’, was no easy feat and required much funding and planning. This was initiated by the now defunct United States Information Agency. It was tacit propaganda, affirming the victory over the Soviets in the race to the moon. But once the Command Module landed in South Kensington, efforts to move it anywhere else seemed too costly and difficult. So the craft settled in.

Although cumbersome, the curators of the museum were more than pleased to receive this important attraction. An internal letter from Dr EJ Becklake remarks, ‘…obviously we must accept. Apollo 10 would be the only authentic manned space capsule on display in Western Europe and, I believe, the only manned capsule to have travelled around the moon on display anywhere outside the States. Its technical content speaks for itself, and the public interest it would arouse would be enormous’. When the Museum came to renew the object’s insurance in 1986, its value was estimated at £1.25 million.

So, pause a moment. What exactly does Apollo 10 say about London? Everything, Ground Control. That our conception of the present, and even the future, is firmly rooted in our remembrances of the past. That more than any American city, perhaps, London is a highly nostalgic place, a city that remembers, albeit not always cognitively. And that looking to the heavens to help us visualise London will evoke metaphors that hint at a certain formlessness of thought. The city as unknowable. And we’re floating, sang Bowie, in a most peculiar way. The truth is stranger than (science) fiction.

By Elizabeth Holdsworth

pirWelcome to my travelling life and why I try to fly premium economy, economy+, extra legroom steats or whatever an airline calls it.

pir*sigh*

By way of an afterwords on Monday's political blog entry, I'd just like to draw your attention to a worrying study that feeds into the issue of political failure modes. The Royal Statistical Society and Ipsos MORI commissioned a poll of public opinion on key social issues. Turns out that the British public are woefully misinformed:

* Teenage pregnancy: public discourse leads people to believe the level is 25 times higher than it actually is

* Crime: 58% don't realize that crime is actually falling

* Benefit fraud: most people think about 24% of social security payments are fraudulently claimed: the actual level of fraud is under 1%

* Foreign aid: more people think foreign aid is one of the top three budget items than the state pension (which accounts for ten times as much expenditure)

* Immigration: the average Brit thinks that 31% of the population are immigrants; even accounting for illegal immigration the figure is under 15%

Even assuming we can fix the damage inflicted on our democratic party system by the growth of the fourth party, how can we hope to elect governments that can engage constructively with actual social problems when the myths believed by the electorate deviate so wildly from the real picture? (And when those myths play so well in the mass media, because bad news makes for such good headlines?)