“Happy anniversary to the worst picture anyone has ever taken of my dog.”

(via source)

The post The Glamorous Life appeared first on AwkwardFamilyPhotos.com.

“Happy anniversary to the worst picture anyone has ever taken of my dog.”

(via source)

The post The Glamorous Life appeared first on AwkwardFamilyPhotos.com.

RobertMaybe Erik can get a job as a dog poop mapper ...

RobertStill ... no thanks.

Visit Olsen Fish Company in North Minneapolis, and Don Sobasky from marketing will offer you a heavy flannel shirt before you’ve even taken off your coat. Not because the heater’s broken, but because of the smell, he’ll explain, while gazing around the 119-year-old seafood processor’s headquarters.

The fish factory itself is inside a separate building on the other side of a parking lot. But the pungent scent of its cod and herring products has seeped over into the main office’s furniture and walls. If guests aren’t careful, their clothes catch the wharfside aroma. Ask Sobasky if his clothes reek after a long day on the job, and he’ll reply, “Well, they smell like money to me.”

Founded in 1910, Olsen Fish Company is the type of niche business that could only exist in the Upper Midwest, where millions of Swedes, Finns, and Norwegians forged new lives in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For decades, the company has served as a cultural heritage lifeline, selling Scandinavian foods such as pickled herring, lingonberries, salt cod, and lefse, a thin potato bread. But Olsen’s most famous—or perhaps infamous—offering has always been lutefisk.

First described by Swedish scholar and archbishop Olaus Magnus in 1555, people have eaten lutefisk in Norway, Sweden, and parts of Finland for centuries, although its popularity has waxed and waned. Lutefisk, when translated from its original Norwegian, is self-explanatory: Lut means lye, and fisk is fish. To make it, dried cod is soaked in caustic lye solution for days, transforming it into quivering fillets.

Nobody quite knows who invented it; tales range from someone accidentally dropping a fish into a bowl of lye to “the Swedes trying to poison the Norwegians,” jokes Travis Dahl, a meat salesman at Ingebretsen's Nordic Marketplace in Minneapolis. Once rinsed, the mild-flavored meat is either baked or boiled, then smothered with everything from melted butter to sautéed onions and bacon bits. The smell can linger long after people clean their plates—an odor that’s the butt of many a Minnesotan grandpa joke.

While fragrant, lutefisk was practical. Early Scandinavians needed protein during their long, cold winters, and lye baths softened dried cod to a chewable consistency. When their descendants—including Olaf Olsen and John Norberg, the Norwegian founders of Olsen Fish Company—came to America, they brought lutefisk with them.

Some Midwestern lutefisk fans chow down on the food year-round. But more commonly, it’s eaten during the midwinter, particularly at Nordic fraternal lodges and Lutheran church suppers. Much of it is sourced from the Olsen Fish Company, which is North America’s largest lutefisk factory. Yet Olsen is one of just a handful of companies still making it: a sign of the delicacy’s decline in popularity.

Olsen president Chris Dorff says the factory produces approximately 400,000 pounds of lutefisk per year. This might sound like a lot, but it’s not for Olsen. “In the late ‘90s, we were probably [selling] half a million pounds,” Dorff says. 30 years ago, Sobasky adds, that number was closer to 800,000.

Olsen’s lutefisk sales are currently slipping at an annual rate of roughly six percent per year. On the whole, Scandinavian-Americans are gradually eating less lutefisk. Lutefisk’s wane can be chalked up to the old guard dying out as younger generations eschew it for tastier alternatives. Other factors include marriage to spouses not reared on lutefisk, and a decline in church attendance (meaning fewer Lutheran lutefisk suppers).

Though the future of its signature staple is unclear, Olsen Fish Company’s bottom line is still strong. As of November 2018, the 18-person business was raking in millions of dollars annually, with lutefisk comprising only 10 to 15 percent of the pie. Most of these sales are herring, which Dorff says appeals to a wide range of buyers. But he chalks up Olsen’s current success to Nigerian-Americans and other West African newcomers. These customers are swiftly supplanting Scandinavians as Olsen’s core customer base, guaranteeing as much as 25 percent of their income. Yet Olsen’s Nigerian clientele aren’t buying lutefisk or herring. Instead, they prefer the dried fish used to make lutefisk.

The reason for why goes back centuries. On northern Norway’s Lofoten Islands, fisheries have long dried fresh cod on wooden racks in the Arctic wind. This desiccation process takes several months, and results in preserved cod, or stockfish. Stockfish can be bathed in lye, becoming lutefisk, but Norwegians also export it sans chemical soak.

Stockfish was nutritious and hardy. It would “remain viable for years and when soaked in water would be reconstituted basically to its original state when caught,” explains Terje Leiren, professor emeritus of Scandinavian Studies at the University of Washington. This made it ideal for long sea voyages, thus indelibly tying it to the transatlantic slave trade—and to Norway, which was once part of a dual monarchy with Denmark. During voyages to the Danish West Indies, today’s United States Virgin Islands, stockfish-laden ships would stop in Nigeria.

Many centuries would pass, though, before stockfish became a West African mainstay. The turning point was the Nigerian Civil War, a bloody conflict in the late 1960s that triggered a humanitarian crisis. Norway shipped “many tons” of stockfish to the eastern secessionist state of Biafra to ease malnutrition, says Moses Ochonu, a professor of African history at Vanderbilt University.

Famine or no famine, stockfish fit into the preexisting culinary tradition. “This kind of intense, slightly fermented flavor was already part of traditional Nigerian cuisine,” Ochonu says. While fermented beans and nuts are used in dishes across the country to supply the desired taste, stockfish’s unique, pungent flavor can’t be provided by locally caught fish. Even better, it’s a protein source that keeps without refrigeration. (That said, Ochonu specifies, stockfish is still more common in eastern Nigerian food than in western and northern Nigeria.)

Today, stockfish is an essential ingredient in Nigerian cuisine, although for some it conjures painful wartime memories. Still imported from northern Norway, it’s cut into chunks, softened in boiling water, and used as a base for Nigerian soups and sauces such as efo riro, spinach soup, edikang ikong, a vegetable soup, and egusi, a soup made with melon seeds.

The Norwegian fish has caught on in other West African countries, too—and when chefs from the region move to the United States, they naturally want to recreate their favorite stockfish dishes. Some buy their fish from African grocery stores. Others rely on purveyors such as Olsen, which first began carrying stockfish nearly 20 years ago after a Nigerian local expressed interest. The gamble ended up paying off in the long run. “Stockfish sales are going up quicker than the lutefisk sales are going down,” Dorff says. “It’s becoming a big part of what we do.”

Twin Cities resident Precious Ojika, who left Nigeria in 1989, had been ordering stockfish from Houston, Texas. Then, she discovered a purveyor in her own backyard. Hip to their shifting base, Olsen Fish Company had secured a booth at the Minnesota IgboFest, an annual Nigerian cultural event. Ojika spotted them there, and realized she “only had to drive 10 miles and pick it up. It was a dream come true.” Even though demand for Olsen’s premier product is on the wane, the company’s spirit is still alive and well. As always, it continues to serve immigrants homesick for familiar foods.

But while the future looks bright for the Olsen Fish Company, what’s the forecast looking like for lutefisk? It might not be selling much, yet its timeless quirk factor may ensure it sticks around among Scandinavian-Americans. “Lutefisk is the weird uncle in the room,” says Gary Legwold, author of The Last Word on Lutefisk: True Tales of Cod and Tradition. Scandinavians are stereotyped as stoic, he says “but just drop the word lutefisk—all you have to do is say the word—and suddenly the room perks up.” Though the jokes may start flying, Legwold concludes they will always lead to reactions of “Oh, I gotta try that.”

In 1979, a group of Iranian college students stormed the American Embassy in Tehran, where they took dozens of hostages. The resulting crisis dominated relations between the two countries, influencing politics for generations. But the tensions proved a boon for American pistachio production. When the American government slapped a retaliatory embargo on Iranian pistachios, California’s nascent pistachio industry exploded, to the point that Iran and the U.S. now are neck and neck for the accolade of the world's top producer.

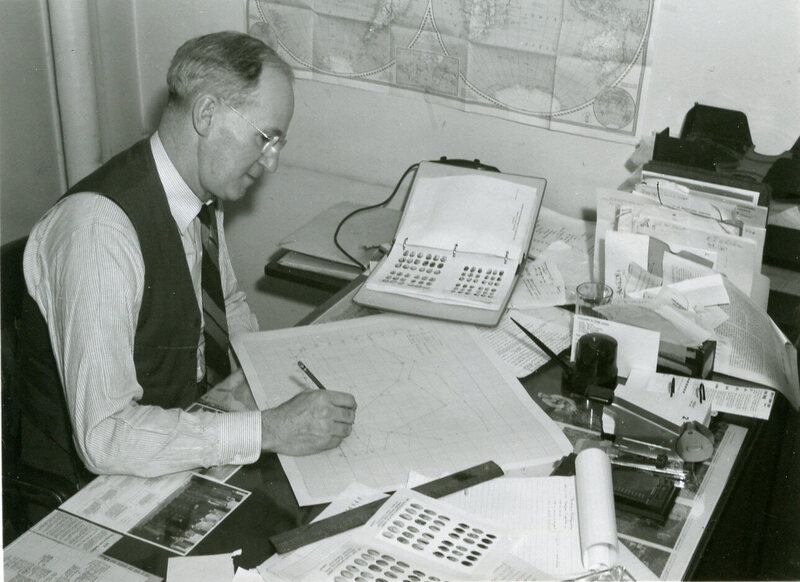

From a botanical perspective, this was a remarkable turnaround. Because only half a century earlier, a “plant explorer” named William E. Whitehouse had seeded the entire industry. In what is now considered “the single most successful plant introduction to the United States in the 20th century,” he traveled to Iran and brought back one very important seed.

While areas in Syria, Turkey, and Sicily have long produced pistachios, Iran’s climate is uniquely suited to the finicky crop. That’s because pistachio trees like extreme conditions—many varieties have deep roots and thick leaves that allow them to grow in hot, drought-prone areas, but they simultaneously require cold winters to fruit. According to Louise Ferguson, a pomologist and pistachio expert at UC Davis, the trees can survive in saline soils that other fruit trees would find insupportable.

The Iranian town of Rafsanjan, in the province of Kerman, is a pistachio-producing powerhouse. It’s desert-like climate and high, chill-inducing altitude make it ideal for pistachios. Most Iranian pistachio farmers hail from Rafsanjan, says Leili Afsah Hejri, a food scientist who specializes in pistachio machinery at the University of Merced. She herself is the fifth generation of a pistachio-producing family from the town.

This concentration of nut knowledge points to another difficulty. Pistachio trees take about a decade to mature, and after they do, many pistachios only produce their trailing bundles of fruit in alternate years. Growing this nut is an investment. (Also, the pistachios we eat aren’t true nuts; they’re seeds.)

These unique requirements are what make pistachios more expensive than most other “nuts.” In fact, they only came to the United States in the late-19th century with Middle Eastern immigrants to New York. But they were imported as “edible nuts,” says Ferguson, “so those were processed and non-fertile.” For decades, imported pistachios were dyed red, as part of an effort to hide blotches. Companies loaded them into train and bus station vending machines, where snackers paid a nickel for a dozen. For years, these vending machines accounted for the vast majority of pistachios sold in the United States.

The botanically inclined experimented with planting the precious trees in the American South and California. But the true start to pistachio domination came with the founding of the Chico New Plant Introduction Station in the early 20th century. Paraphrasing a favorite sci-fi quote, Ferguson says that part of the USDA’s goal is to explore “new worlds” of plants. In 1929, the station sent William E. Whitehouse, a deciduous tree researcher, to Iran. His mission: to collect pistachio seeds for planting.

For six months, Whitehouse searched, gradually collecting 20 pounds of different pistachios. Some came from the Agah family in Rafsanjan, who, Hejri notes, is still the main producer of pistachios in the area. After Whitehouse’s return to Chico, the station planted and evaluated 3,000 trees. Only one pistachio rose above the others. Sourced from the Agah orchard, it was given the name “Kerman.”

“That became the basis of our industry,” says Ferguson. Its virtues are many. “They’re round in shape, they’re unstained and clean-shelled, firm, crispy, purple and yellowish-green kerneled … ” Hejri rhapsodises. Provided with a nearby male “Peters” tree for fertilization, the Kerman would become the American pistachio. A female mother tree at the Chico research station, planted around 1931, became the source of “all commercial pistachio trees in California,” writes journalist Eric Hansen. In Iran, more than 50 varieties are cultivated, not counting the great number of wild pistachios. But even today, the vast majority of California’s pistachio trees are Kerman.

Eventually, California’s San Joaquin Valley would become the Rafsanjan of America. Summer temperatures in the national breadbasket can be roasting, but the “winter fogs serve the same purpose that chill from altitude served in Iran,” Ferguson notes.

But progress was slow, and pistachio planting stayed small-scale for decades. Whitehouse kept his eye on the pistachio as a potential money crop for California, publishing a paper on the subject in 1957. He noted that while the Iranian pistachio had been an important local crop for hundreds of years, its value as an export was recognized only in the first half of the 20th century, “with new plantings keeping pace with the rapid increase in American consumption.” But despite the demand, it took two more decades for the first commercial crop of American pistachios to be harvested in 1976.

Yet the true reason for the success of the American pistachio was political, rather than botanical. In the early ‘70s, California growers turned to pistachio plantings when citrus and almond groves were increasingly taxed—an effort aided by the Central Valley Project bringing needed water. Then, a decade later, the friction with Iran resulted in sanctions on Iranian pistachios. “This California pistachio is brought to you courtesy of the Internal Revenue Service and the Shah of Iran,” the New York Times noted in 1979. Even after sanctions were lifted, Ferguson adds, the pistachio industry “organized very quickly and got a 300 percent tariff against the Iranian product.”

Whitehouse died in 1982, less than a decade after pistachios became a commercial crop. Though considered the father of the American pistachio industry, he’s never received much renown for his accomplishments. He did, however, have a pear (of all things) named in his honor, and received the first very-new Pistachio Association's Annual Achievement to Industry Award in 1977. That year, only 1,700 acres were planted with producing trees. By 2012, that number had ballooned to 178,000 acres. It seems like small pistachios in light of his accomplishment: laying the groundwork for an industry worth $1.6 billion in California alone, and finding a new home for an in-demand tree.

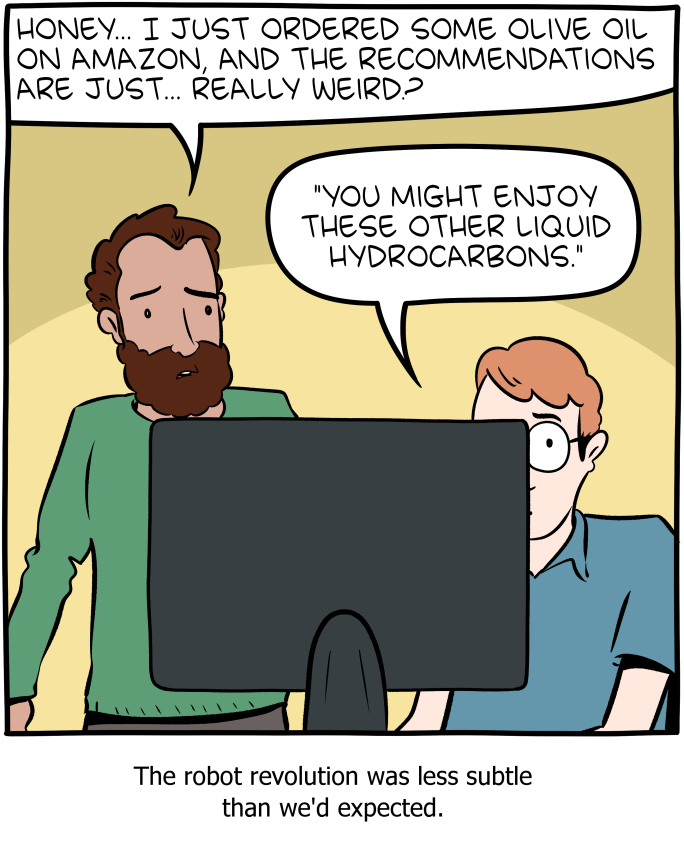

Hovertext:

The weird part is when yelp recommends for you to go drink borax and you do it because they've never been wrong in the past.

RobertI think you would rate it terrible.

It seems cruel to make someone test recipes while they are sick, and this week Tom had the flu. So I made him a nice bowl of hot chicken noodle soup.

With Fried Bananas on top!

This was one of those crazy topping ideas I got from a 1941 book entitled, Easy Ways To Good Meals: 99 Delicious Dishes Made With Campbell’s Condensed Soups. (Buy on eBay here! *affiliate link) Which might be surprising, because this sounds like something from a Chiquita banana cookbook. But no, it’s from Campbells. I briefly thought about using actual Campbell’s Soup, but I figured that it wouldn’t make difference if I used homemade or not, since I am sure Campbell’s soup is not the same as it was in 1941 anyway.

I even tried getting fancy with the bananas, and scoring them with a fork like you do for “fancy” cucumbers.

But honestly, it made no difference. You couldn’t tell the “fancied” bananas from the regular ones after they were cooked.

Here we are! All loaded onto soup. I made my “get better quick chicken soup”, which is a rotisserie chicken from the store, bone broth (you can use store-bought) and veggie stock. Then egg noodles, carrots, celery, onion and as much fresh garlic and ginger as you can handle. Pro-tip: Buy a big bunch of celery and use all of the celery leaves, too. They really make a difference!

“What the heck is this?”

“Bananas.”

“But it’s just chicken soup under it, right?”

“Yes.”

“Are you lying?”

“It’s just soup, I promise.”

“Well? How is it? Is your mind blown?”

“It’s not terrible.”

“Well, that’s a ringing endorsement.”

“What do you want from me? It’s bananas in chicken noodle soup.”

From The Tasting Notes –

If you are looking for an “interesting” way to garnish your soup and use up a banana, you could do worse than this. The banana was sweet and a little salty (I used salted butter), and was an interesting contrast to soup. If you got the banana with a bite of chicken, it was better. It might have actually been better with canned condensed soup, because there aren’t any veggies in that. But not something that I am probably ever going to do again. At least in this form. The soup needs to be spicer to work with the bananas, I think. Or maybe do it with a plantain. In an interesting side note, I piled the rest of the bananas into a bowl by themselves and divided them up between the kids to eat straight, and they loved them. Alex said it “tastes like banana pie” and TJ ate his up in a flash. So, if you have that banana or two laying around needing to be used up and it’s too cold for smoothies, maybe just fry it up for your kids for dessert instead of floating it in canned soup.

RobertMaybe if Tim kills our Pathfinder characters off at the same time our new characters can be twins.

Hovertext:

We'll keep having more kids until we reach Benjamoptimal.

RobertDo we try this with Annika?

“Okay, Mom, my room is clean!” You know before you even see the finished product that your child’s room is most definitely not clean. And, sure enough, when you poke your head in the door, you see the same thing you always see after they’ve supposedly cleaned their room: A big clear spot in the center of the floor and…

As a parent who works from home, screen time is always a topic of discussion in our household, especially during summer and winter breaks. Because my work requires me to actually concentrate without the sounds of kids asking for snacks and bickering over who has control of the Netflix queue, I had to come up with a…

.png)

Hovertext:

One of the negative consequences of widespread irreligion has been the loss of ability to properly tell off malfunctioning software.