The mind…can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven. ― John Milton

The mind is certainly its own cosmos. — Alan Lightman

________

You go to school, study hard, get a degree, and you’re pleased with yourself. But are you wiser?

You get a job, achieve things at the job, gain responsibility, get paid more, move to a better company, gain even more responsibility, get paid even more, rent an apartment with a parking spot, stop doing your own laundry, and you buy one of those $9 juices where the stuff settles down to the bottom. But are you happier?

You do all kinds of life things—you buy groceries, read articles, get haircuts, chew things, take out the trash, buy a car, brush your teeth, shit, sneeze, shave, stretch, get drunk, put salt on things, have sex with someone, charge your laptop, jog, empty the dishwasher, walk the dog, buy a couch, close the curtains, button your shirt, wash your hands, zip your bag, set your alarm, fix your hair, order lunch, act friendly to someone, watch a movie, drink apple juice, and put a new paper towel roll on the thing.

But as you do these things day after day and year after year, are you improving as a human in a meaningful way?

In the last post, I described the way my own path had led me to be an atheist—but how in my satisfaction with being proudly nonreligious, I never gave serious thought to an active approach to internal improvement—hindering my own evolution in the process.

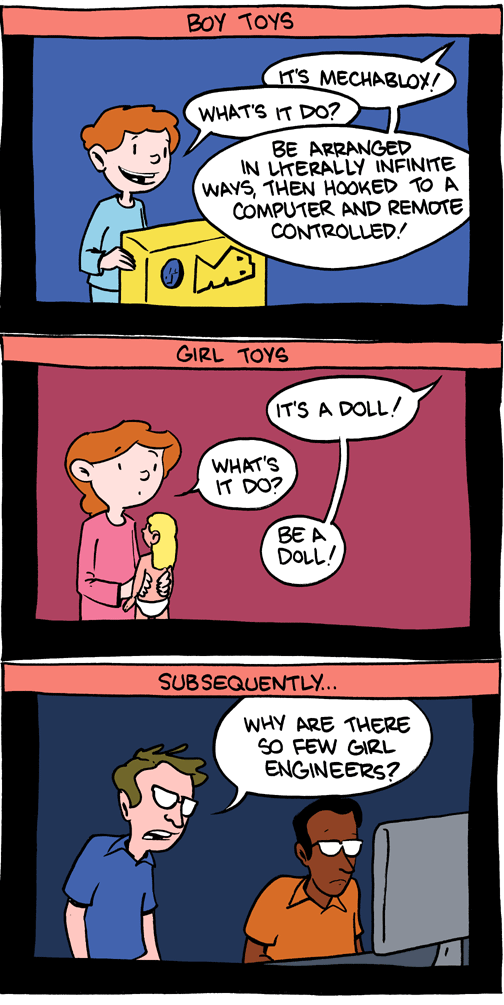

This wasn’t just my own naiveté at work. Society at large focuses on shallow things, so it doesn’t stress the need to take real growth seriously. The major institutions in the spiritual arena—religions—tend to focus on divinity over people, making salvation the end goal instead of self-improvement. The industries that do often focus on the human condition—philosophy, psychology, art, literature, self-help, etc.—lie more on the periphery, with their work often fragmented from each other. All of this sets up a world that makes it hard to treat internal growth as anything other than a hobby, an extra-curricular, icing on the life cake.

Considering that the human mind is an ocean of complexity that creates every part of our reality, working on what’s going on in there seems like it should be a more serious priority. In the same way a growing business relies on a clear mission with a well thought-out strategy and measurable metrics, a growing human needs a plan—if we want to meaningfully improve, we need to define a goal, understand how to get there, become aware of obstacles in the way, and have a strategy to get past them.

When I dove into this topic, I thought about my own situation and whether I was improving. The efforts were there—apparent in many of this blog’s post topics—but I had no growth model, no real plan, no clear mission. Just kind of haphazard attempts at self-improvement in one area or another, whenever I happened to feel like it. So I’ve attempted to consolidate my scattered efforts, philosophies, and strategies into a single framework—something solid I can hold onto in the future—and I’m gonna use this post to do a deep dive into it.

So settle in, grab some coffee, and get your brain out and onto the table in front of you—you’ll want to have it there to reference as we explore what a weird, complicated object it is.

____________

The Goal

Wisdom. More on that later.

How Do We Get to the Goal?

By being aware of the truth. When I say “the truth,” I’m not being one of those annoying people who says the word truth to mean some amorphous, mystical thing—I’m just referring to the actual facts of reality. The truth is a combination of what we know and what we don’t know—and gaining and maintaining awareness of both sides of this reality is the key to being wise.

Easy, right? We don’t have to know more than we know, we only have to be aware of what we know and what we don’t know. Truth is in plain sight, written on the whiteboard—we just have to look at the board and reflect upon it. There’s just this one thing—

What’s in Our Way?

The fog.

To understand the fog, let’s first be clear that we’re not here:

We’re here:

And this isn’t the situation:

This is:

This is a really hard concept for humans to absorb, but it’s the starting place for growth. Declaring ourselves “conscious” allows us to call it a day and stop thinking about it. I like to think of it as a consciousness staircase:

An ant is more conscious than a bacterium, a chicken more than an ant, a monkey more than a chicken, and a human more than a monkey. But what’s above us?

A) Definitely something, and B) Nothing we can understand better than a monkey can understand our world and how we think.

There’s no reason to think the staircase doesn’t extend upwards forever. The red alien a few steps above us on the staircase would see human consciousness the same way we see that of an orangutan—they might think we’re pretty impressive for an animal, but that of course we don’t actually begin to understand anything. Our most brilliant scientist would be outmatched by one of their toddlers.

To the green alien up there higher on the staircase, the red alien might seem as intelligent and conscious as a chicken seems to us. And when the green alien looks at us, it sees the simplest little pre-programmed ants.

We can’t conceive of what life higher on the staircase would be like, but absorbing the fact that higher stairs exist and trying to view ourselves from the perspective of one of those steps is the key mindset we need to be in for this exercise.

For now, let’s ignore those much higher steps and just focus on the step right above us—that light green step. A species on that step might see us like a three-year-old child—emerging into consciousness through a blur of simplicity and naiveté. Let’s imagine that a representative from that species was sent to observe humans and report back to his home planet about them—what would he think of the way we thought and behaved? What about us would impress him? What would make him cringe?

I think he’d very quickly see a conflict going on in the human mind. On one hand, all of those steps on the staircase below the human are where we grew from. Hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary adaptations geared toward animal survival in a rough world are very much rooted in our DNA, and the primitive impulses in us have birthed a bunch of low-grade qualities—fear, pettiness, jealousy, greed, instant-gratification, etc. Those qualities are the remnants of our animal past and still a prominent part of our brains, creating a zoo of small-minded emotions and motivations in our heads:

But over the past six million years, our evolutionary line has experienced a rapid growth in consciousness and the incredible ability to reason in a way no other species on Earth can. We’ve taken a big step up the consciousness staircase, very quickly—let’s call this burgeoning element of higher consciousness our Higher Being.

The Higher Being is brilliant, big-thinking, and totally rational. But on the grand timescale, he’s a very new resident in our heads, while the primal animal forces are ancient, and their coexistence in the human mind makes it a strange place:

So it’s not that a human is the Higher Being and the Higher Being is three years old—it’s that a human is the combination of the Higher Being and the low-level animals, and they blend into the three-year-old that we are. The Higher Being alone would be a more advanced species, and the animals alone would be one far more primitive, and it’s their particular coexistence that makes us distinctly human.

As humans evolved and the Higher Being began to wake up, he looked around your brain and found himself in an odd and unfamiliar jungle full of powerful primitive creatures that didn’t understand who or what he was. His mission was to give you clarity and high-level thought, but with animals tramping around his work environment, it wasn’t an easy job. And things were about to get much worse. Human evolution continued to make the Higher Being more and more sentient, until one day, he realized something shocking:

WE’RE GOING TO DIE

It marked the first time any species on planet Earth was conscious enough to understand that fact, and it threw all of those animals in the brain—who were not built to handle that kind of information—into a complete frenzy, sending the whole ecosystem into chaos:

The animals had never experienced this kind of fear before, and their freakout about this—one that continues today—was the last thing the Higher Being needed as he was trying to grow and learn and make decisions for us.

The adrenaline-charged animals romping around our brain can take over our mind, clouding our thoughts, judgment, sense of self, and understanding of the world. The collective force of the animals is what I call “the fog.” The more the animals are running the show and making us deaf and blind to the thoughts and insights of the Higher Being, the thicker the fog is around our head, often so thick we can only see a few inches in front of our face:

Let’s think back to our goal above and our path to it—being aware of the truth. The Higher Being can see the truth just fine in almost any situation. But when the fog is thick around us, blocking our eyes and ears and coating our brain, we have no access to the Higher Being or his insight. This is why being continually aware of the truth is so hard—we’re too lost in the fog to see it or think about it.

And when the alien representative is finished observing us and heads back to his home planet, I think this would be his sum-up of our problems:

The battle of the Higher Being against the animals—of trying to see through the fog to clarity—is the core internal human struggle.

This struggle in our heads takes place on many fronts. We’ve examined a few of them here: the Higher Being (in his role as the Rational Decision Maker) fighting the Instant Gratification Monkey; the Higher Being (in the role of the Authentic Voice) battling against the overwhelmingly scared Social Survival Mammoth; the Higher Being’s message that life is just a bunch of Todays getting lost in the blinding light of fog-based yearning for better tomorrows. Those are all part of the same core conflict between our primal past and our enlightened future.

The shittiest thing about the fog is that when you’re in the fog, it blocks your vision so you can’t see that you’re in the fog. It’s when the fog is thickest that you’re the least aware that it’s there at all—it makes you unconscious. Being aware that the fog exists and learning how to recognize it is the key first step to rising up in consciousness and becoming a wiser person.

So we’ve established that our goal is wisdom, that to get there we need to become as aware as possible of the truth, and that the main thing standing in our way is the fog. Let’s zoom in on the battlefield to look at why “being aware of the truth” is so important and how we can overcome the fog to get there:

The Battlefield

No matter how hard we tried, it would be impossible for humans to access that light green step one above us on the consciousness staircase. Our advanced capability—the Higher Being—just isn’t there yet. Maybe in a million years or two. For now, the only place this battle can happen is on the one step where we live, so that’s where we’re going to zoom in. We need to focus on the mini spectrum of consciousness within our step, which we can do by breaking our step down into four substeps:

Climbing this mini consciousness staircase is the road to truth, the way to wisdom, my personal mission for growth, and a bunch of other cliché statements I never thought I’d hear myself say. We just have to understand the game and work hard to get good at it.

Let’s look at each step to try to understand the challenges we’re dealing with and how we can make progress:

Step 1: Our Lives in the Fog

Step 1 is the lowest step, the foggiest step, and unfortunately, for most of us it’s our default level of existence. On Step 1, the fog is all up in our shit, thick and close and clogging our senses, leaving us going through life unconscious. Down here, the thoughts, values, and priorities of the Higher Being are completely lost in the blinding fog and the deafening roaring, tweeting, honking, howling, and squawking of the animals in our heads. This makes us 1) small-minded, 2) short-sighted, and 3) stupid. Let’s discuss each of these:

1) On Step 1, you’re terribly small-minded because the animals are running the show.

When I look at the wide range of motivating emotions that humans experience, I don’t see them as a scattered range, but rather falling into two distinct bins: the high-minded, love-based, advanced emotions of the Higher Being, and the small-minded, fear-based, primitive emotions of our brain animals.

And on Step 1, we’re completely intoxicated by the animal emotions as they roar at us through the dense fog.

This is what makes us petty and jealous and what makes us so thoroughly enjoy the misfortune of others. It’s what makes us scared, anxious, and insecure. It’s why we’re self-absorbed and narcissistic; vain and greedy; narrow-minded and judgmental; cold, callous, and even cruel. And only on Step 1 do we feel that primitive “us versus them” tribalism that makes us hate people different than us.

You can find most of these same emotions in a clan of capuchin monkeys—and that makes sense, because at their core, these emotions can be boiled down to the two keys of animal survival: self-preservation and the need to reproduce.

Step 1 emotions are brutish and powerful and grab you by the collar, and when they’re upon you, the Higher Being and his high-minded, love-based emotions are shoved into the sewer.

2) On Step 1, you’re short-sighted, because the fog is six inches in front of your face, preventing you from seeing the big picture.

The fog explains all kinds of totally illogical and embarrassingly short-sighted human behavior.

Why else would anyone ever take a grandparent or parent for granted while they’re around, seeing them only occasionally, opening up to them only rarely, and asking them barely any questions—even though after they die, you can only think about how amazing they were and how you can’t believe you didn’t relish the opportunity to enjoy your relationship with them and get to know them better when they were around?

Why else would people brag so much, even though if they could see the big picture, it would be obvious that everyone finds out about the good things in your life eventually either way—and that you always serve yourself way more by being modest?

Why else would someone do the bare minimum at work, cut corners on work projects, and be dishonest about their efforts—when anyone looking at the big picture would know that in a work environment, the truth about someone’s work habits eventually becomes completely apparent to both bosses and colleagues, and you’re never really fooling anyone? Why would someone insist on making sure everyone knows when they did something valuable for the company—when it should be obvious that acting that way is transparent and makes it seem like you’re working hard just for the credit, while just doing things well and having one of those things happen to be noticed does much more for your long term reputation and level of respect at the company?

If not for thick fog, why would anyone ever pinch pennies over a restaurant bill or keep an unpleasantly-rigid scorecard of who paid for what on a trip, when everyone reading this could right now give each of their friends a quick and accurate 1-10 rating on the cheap-to-generous (or selfish-to-considerate) scale, and the few hundred bucks you save over time by being on the cheap end of the scale is hardly worth it considering how much more likable and respectable it is to be generous?

What other explanation is there for the utterly inexplicable decision by so many famous men in positions of power to bring down the career and marriage they spent their lives building by having an affair?

And why would anyone bend and loosen their integrity for tiny insignificant gains when integrity affects your long-term self esteem and tiny insignificant gains affect nothing in the long term?

How else could you explain the decision by so many people to let the fear of what others might think dictate the way they live, when if they could see clearly they’d realize that A) that’s a terrible reason to do or not do something, and B) no one’s really thinking about you anyway—they’re buried in their own lives.

And then there are all the times when someone’s opaque blinders keep them in the wrong relationship, job, city, apartment, friendship, etc. for years, sometimes decades, only for them to finally make a change and say “I can’t believe I didn’t do this earlier,” or “I can’t believe I couldn’t see how wrong that was for me.” They should absolutely believe it, because that’s the power of the fog.

3) On Step 1, you’re very, very stupid.

One way this stupidity shows up is in us making the same obvious mistakes over and over and over again.1

The most glaring example is the way the fog convinces us, time after time after time, that certain things will make us happy that in reality absolutely don’t. The fog lines up a row of carrots, tells us that they’re the key to happiness, and tells us to forget today’s happiness in favor of directing all of our hope to all the happiness the future will hold because we’re gonna get those carrots.

And even though the fog has proven again and again that it has no idea how human happiness works—even though we’ve had so many experiences finally getting a carrot and feeling a ton of temporary happiness, only to watch that happiness fade right back down to our default level a few days later—we continue to fall for the trick.

It’s like hiring a nutritionist to help you with your exhaustion, and they tell you that the key is to drink an espresso shot anytime you’re tired. So you’d try it and think the nutritionist was a genius until an hour later when it dropped you like an anvil back into exhaustion. You go back to the nutritionist, who gives you the same advice, so you try it again and the same thing happens. That would probably be it right? You’d fire the nutritionist. Right? So why are we so gullible when it comes to the fog’s advice on happiness and fulfillment?

The fog is also much more harmful than the nutritionist because not only does it give us terrible advice—but the fog itself is the source of unhappiness. The only real solution to exhaustion is to sleep, and the only real way to improve happiness in a lasting way is to make progress in the battle against the fog.

There’s a concept in psychology called The Hedonic Treadmill, which suggests that humans have a stagnant default happiness level and when something good or bad happens, after an initial change in happiness, we always return to that default level. And on Step 1, this is completely true of course, given that trying to become permanently happier while in the fog is like trying to dry your body off while standing under the shower with the water running.

But I refuse to believe the same species that builds skyscrapers, writes symphonies, flies to the moon, and understands what a Higgs boson is is incapable of getting off the treadmill and actually improving in a meaningful way.

I think the way to do it is by learning to climb this consciousness staircase to spend more of our time on Steps 2, 3, and 4, and less of it mired unconsciously in the fog.

Step 2: Thinning the Fog to Reveal Context

Humans can do something amazing that no other creature on Earth can do—they can imagine. If you show an animal a tree, they see a tree. Only a human can imagine the acorn that sunk into the ground 40 years earlier, the small flimsy stalk it was at three years old, how stark the tree must look when it’s winter, and the eventual dead tree lying horizontally in that same place.

This is the magic of the Higher Being in our heads.

On the other hand, the animals in your head, like their real world relatives, can only see a tree, and when they see one, they react instantly to it based on their primitive needs. When you’re on Step 1, your unconscious animal-run state doesn’t even remember that the Higher Being exists, and his genius abilities go to waste.

Step 2 is all about thinning out the fog enough to bring the Higher Being’s thoughts and abilities into your consciousness, allowing you to see behind and around the things that happen in life. Step 2 is about bringing context into your awareness, which reveals a far deeper and more nuanced version of the truth.

There are plenty of activities or undertakings that can help thin out your fog. To name three:

1) Learning more about the world through education, travel, and life experience—as your perspective broadens, you can see a clearer and more accurate version of the truth.

2) Active reflection. This is what a journal can help with, or therapy, which is basically examining your own brain with the help of a fog expert. Sometimes a hypothetical question can be used as “fog goggles,” allowing you to see something clearly through the fog—questions like, “What would I do if money were no object?” or “How would I advise someone else on this?” or “Will I regret not having done this when I’m 80?” These questions are a way to ask your Higher Being’s opinion on something without the animals realizing what’s going on, so they’ll stay calm and the Higher Being can actually talk—like when parents spell out a word in front of their four-year-old when they don’t want him to know what they’re saying.2

3) Meditation, exercise, yoga, etc.—activities that help quiet the brain’s unconscious chatter, i.e. allowing the fog to settle.

But the easiest and most effective way to thin out the fog is simply to be aware of it. By knowing that fog exists, understanding what it is and the different forms it takes, and learning to recognize when you’re in it, you hinder its ability to run your life. You can’t get to Step 2 if you don’t know when you’re on Step 1.

The way to move onto Step 2 is by remembering to stay aware of the context behind and around what you see, what you come across, and the decisions you make. That’s it—remaining cognizant of the fog and remembering to look at the whole context keeps you conscious, aware of reality, and as you’ll see, makes you a much better version of yourself than you are on Step 1. Some examples—

Here’s what a rude cashier looks like on Step 1 vs. Step 2:

Here’s what gratitude looks like:

Something good happening:

Something bad happening:

That phenomenon where everything suddenly seems horrible late at night in bed:

A flat tire:

Long-term consequences:

Looking at context makes us aware how much we actually know about most situations (as well as what we don’t know, like what the cashier’s day was like so far), and it reminds us of the complexity and nuance of people, life, and situations. When we’re on Step 2, this broader scope and increased clarity makes us feel calmer and less fearful of things that aren’t actually scary, and the animals—who gain their strength from fear and thrive off of unconsciousness—suddenly just look kind of ridiculous:

When the small-minded animal emotions are less in our face, the more advanced emotions of the Higher Being—love, compassion, humility, empathy, etc.—begin to light up.

The good news is there’s no learning required to be on Step 2—your Higher Being already knows the context around all of these life situations. It doesn’t take hard work, and no additional information or expertise is needed—you only have to consciously think about being on Step 2 instead of Step 1 and you’re there. You’re probably there right now just by reading this.

The bad news is that it’s extremely hard to stay on Step 2 for long. The Catch-22 here is that it’s not easy to stay conscious of the fog because the fog makes you unconscious.

That’s the first challenge at hand. You can’t get rid of the fog, and you can’t always keep it thin, but you can get better at noticing when it’s thick and develop effective strategies for thinning it out whenever you consciously focus on it. If you’re evolving successfully, as you get older, you should be spending more and more time on Step 2 and less and less on Step 1.

Step 3: Shocking Reality

I . . . a universe of atoms . . . an atom in the universe. —Richard Feynman

_________

Step 3 is when things start to get weird. Even on the more enlightened Step 2, we kind of think we’re here:

As delightful as that is, it’s a complete delusion. We live our days as if we’re just here on this green and brown land with our blue sky and our chipmunks and our caterpillars. But this is actually what’s happening:

But even more actually, this is happening:

We also tend to kind of think this is the situation:

When really, it’s this:

You might even think you’re a thing. Do you?

No you’re a ton of these:

This is the next iteration of truth on our little staircase, and our brains can’t really handle it. Asking a human to internalize the vastness of space or the eternity of time or the tininess of atoms is like asking a dog to stand up on its hind legs—you can do it if you focus, but it’s a strain and you can’t hold it for very long.3

You can think about the facts anytime—The Big Bang was 13.8 billion years ago, which is about 130,000 times longer than humans have existed; if the sun were a ping pong ball in New York, the closest star to us would be a ping pong ball in Atlanta; the Milky Way is so big that if you made a scale model of it that was the size of the US, you would still need a microscope to see the sun; atoms are so small that there are about as many atoms in one grain of salt as there are grains of sand on all the beaches on Earth. But once in a while, when you deeply reflect on one of these facts, or when you’re in the right late night conversation with the right person, or when you’re staring at the stars, or when you think too hard about what death actually means—you have a Whoa moment.

A true Whoa moment is hard to come by and even harder to maintain for very long, like our dog’s standing difficulties. Thinking about this level of reality is like looking at an amazing photo of the Grand Canyon; a Whoa moment is like being at the Grand Canyon—the two experiences are similar but somehow vastly different. Facts can be fascinating, but only in a Whoa moment does your brain actually wrap itself around true reality. In a Whoa moment, your brain for a second transcends what it’s been built to do and offers you a brief glimpse into the astonishing truth of our existence. And a Whoa moment is how you get to Step 3.

I love Whoa moments. They make me feel some intense combination of awe, elation, sadness, and wonder. More than anything, they make me feel ridiculously, profoundly humble—and that level of humility does weird things to a person. In those moments, all those words religious people use—awe, worship, miracle, eternal connection—make perfect sense. I want to get on my knees and surrender. This is when I feel spiritual.

And in those fleeting moments, there is no fog—my Higher Being is in full flow and can see everything in perfect clarity. The normally-complicated world of morality is suddenly crystal clear, because the only fathomable emotions on Step 3 are the most high-level. Any form of pettiness or hatred is a laughable concept up on Step 3—with no fog to obscure things, the animals are completely naked, exposed for the sad little creatures that they are.

On Step 1, I snap back at the rude cashier, who had the nerve to be a dick to me. On Step 2, the rudeness doesn’t faze me because I know it’s about him, not me, and that I have no idea what his day or life has been like. On Step 3, I see myself as a miraculous arrangement of atoms in vast space that for a split second in endless eternity has come together to form a moment of consciousness that is my life…and I see that cashier as another moment of consciousness that happens to exist on the same speck of time and space that I do. And the only possible emotion I could have for him on Step 3 is love.

In a Whoa moment’s transcendent level of consciousness, I see every interaction, every motivation, every news headline in unusual clarity—and difficult life decisions are much more obvious. I feel wise.

Of course, if this were my normal state, I’d be teaching monks somewhere on a mountain in Myanmar, and I’m not teaching any monks anywhere because it’s not my normal state. Whoa moments are rare and very soon after one, I’m back down here being a human again. But the emotions and the clarity of Step 3 are so powerful, that even after you topple off the step, some of it sticks around. Each time you humiliate the animals, a little bit of their future power over you is diminished. And that’s why Step 3 is so important—even though no one that I know can live permanently on Step 3, regular visits help you dramatically in the ongoing Step 1 vs Step 2 battle, which makes you a better and happier person.

Step 3 is also the answer to anyone who accuses atheists of being amoral or cynical or nihilistic, or wonders how atheists find any meaning in life without the hope and incentive of an afterlife. That’s a Step 1 way to view an atheist, where life on Earth is taken for granted and it’s assumed that any positive impulse or emotion must be due to circumstances outside of life. On Step 3, I feel immensely lucky to be alive and can’t believe how cool it is that I’m a group of atoms that can think about atoms—on Step 3, life itself is more than enough to make me excited, hopeful, loving, and kind. But Step 3 is only possible because science has cleared the way there, which is why Carl Sagan said that “science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality.” In this way, science is the “prophet” of this framework—the one who reveals new truth to us and gives us an opportunity to alter ourselves by accessing it.

So to recap so far—on Step 1, you’re in a delusional bubble that Step 2 pops. On Step 2, there’s much more clarity about life, but it’s within a much bigger delusional bubble, one that Step 3 pops. But Step 3 is supposed to be total, fog-free clarity on truth—so how could there be another step?

Step 4: The Great Unknown

If we ever reach the point where we think we thoroughly understand who we are and where we came from, we will have failed. —Carl Sagan

_________

The game so far has for the most part been clearing out fog to become as conscious as possible of what we as people and as a species know about truth:

On Step 4, we’re reminded of the complete truth—which is this:

The fact is, any discussion of our full reality—of the truth of the universe or our existence—is a complete delusion without acknowledging that big purple blob that makes up almost all of that reality.

But you know humans—they don’t like that purple blob one bit. Never have. The blob frightens and humiliates humans, and we have a rich history of denying its existence entirely, which is like living on the beach and pretending the ocean isn’t there. Instead, we just stamp our foot and claim that now we’ve finally figured it all out. On the religious side, we invent myths and proclaim them as truth—and even a devout religious believer reading this who stands by the truth of their particular book would agree with me about the fabrication of the other few thousand books out there. On the science front, we’ve managed to be consistently gullible in believing that “realizing you’ve been horribly wrong about reality” is a phenomenon only of the past.

Having our understanding of reality overturned by a new groundbreaking discovery is like a shocking twist in this epic mystery novel humanity is reading, and scientific progress is regularly dotted with these twists—the Earth being round, the solar system being heliocentric, not geocentric, the discovery of subatomic particles or galaxies other than our own, and evolutionary theory, to name a few. So how is it possible, with the knowledge of all those breakthroughs, that Lord Kelvin, one of history’s greatest scientists, said in the year 1900, “There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement”4—i.e. this time, all the twists actually are finished.

Of course, Kelvin was as wrong as every other arrogant scientist in history—the theory of general relativity and then the theory of quantum mechanics would both topple science on its face over the next century.

Even if we acknowledge today that there will be more twists in the future, we’re probably kind of inclined to think we’ve figured out most of the major things and have a far closer-to-complete picture of reality than the people who thought the Earth was flat. Which, to me, sounds like this:

The fact is, let’s remember that we don’t know what the universe is. Is it everything? Is it one tiny bubble in a multiverse frothing with bubbles? Is it not a bubble at all but an optical illusion hologram? And we know about the Big Bang, but was that the beginning of everything? Did something arise from nothing, or was it just the latest in a long series of expansion/collapse cycles?5 We have no clue what dark matter is, only that there’s a shit-ton of it in the universe, and when we discussed The Fermi Paradox, it became entirely clear that science has no idea about whether there’s other life out there or how advanced it might be. How about String Theory, which claims to be the secret to unifying the two grand but seemingly-unrelated theories of the physical world, general relativity and quantum mechanics? It’s either the grandest theory we’ve ever come up with or totally false, and there are great scientists on both sides of this debate. And as laypeople, all we need to do is take a look at those two well-accepted theories to realize how vastly different reality can be from how it seems: like general relativity telling us that if you flew to a black hole and circled around it a few times in intense gravity and then returned to Earth a few hours after you left, decades would have passed on Earth while you were gone. And that’s like an ice cream cone compared to the insane shit quantum mechanics tells us—like two particles across the universe from one another being mysteriously linked to each other’s behavior, or a cat that’s both alive and dead at the same time, until you look at it.

And the thing is, everything I just mentioned is still within the realm of our understanding. As we established earlier, compared to a more evolved level of consciousness, we might be like a three-year-old, a monkey, or an ant—so why would we assume that we’re even capable of understanding everything in that purple blob? A monkey can’t understand that the Earth is a round planet, let alone that the solar system, galaxy, or universe exists. You could try to explain it to a monkey for years and it wouldn’t be possible. So what are we completely incapable of grasping even if a more intelligent species tried its hardest to explain it to us? Probably almost everything.

There are really two options when thinking about the big, big picture: be humble or be absurd.

The nonsensical thing about humans feigning certainty because we’re scared is that in the old days, when it seemed on the surface that we were the center of all creation, uncertainty was frightening because it made our reality seem so much bleaker than we had thought—but now, with so much more uncovered, things look highly bleak for us as people and as a species, so our fear should welcome uncertainty. Given my default outlook that I have a small handful of decades left and then an eternity of nonexistence, the fact that we might be totally wrong sounds tremendously hopeful to me.

Ironically, when my thinking reaches the top of this rooted-in-atheism staircase, the notion that something that seems divine to us might exist doesn’t seem so ridiculous anymore. I’m still totally atheist when it comes to all human-created conceptions of a divine higher force—which all, in my opinion, proclaim far too much certainty. But could a super-advanced force exist? It seems more than likely. Could we have been created by something/someone bigger than us or be living as part of a simulation without realizing it? Sure—I’m a three-year-old, remember, so who am I to say no?

To me, complete rational logic tells me to be atheist about all of the Earth’s religions and utterly agnostic about the nature of our existence or the possible existence of a higher being. I don’t arrive there via any form of faith, just by logic.

I find Step 4 mentally mind-blowing but I’m not sure I’m ever quite able to access it in a spiritual way like I sometimes can with Step 3—Step 4 Whoa moments might be reserved for Einstein-level thinkers—but even if I can’t get my feet up on Step 4, I can know it’s there, what it means, and I can remind myself of its existence. So what does that do for me as a human?

Well remember that powerful humility I mentioned in Step 3? It multiples that by 100. For reasons I just discussed, it makes me feel more hopeful. And it leaves me feeling pleasantly resigned to the fact that I will never understand what’s going on, which makes me feel like I can take my hand off the wheel, sit back, relax, and just enjoy the ride. In this way, I think Step 4 can make us live more in the present—if I’m just a molecule floating around an ocean I can’t understand, I might as well just enjoy it.

The way Step 4 can serve humanity is by helping to crush the notion of certainty. Certainty is primitive, leads to “us versus them” tribalism, and starts wars. We should be united in our uncertainty, not divided over fabricated certainty. And the more humans turn around and look at that big purple blob, the better off we’ll be.

Why Wisdom is the Goal

Nothing clears fog like a deathbed, which is why it’s then that people can always see with more clarity what they should have done differently—I wish I had spent less time working; I wish I had communicated with my wife more; I wish I had traveled more; etc. The goal of personal growth should be to gain that deathbed clarity while your life is still happening so you can actually do something about it.

The way you do that is by developing as much wisdom as possible, as early as possible. To me, wisdom is the most important thing to work towards as a human. It’s the big objective—the umbrella goal under which all other goals fall into place. I believe I have one and only one chance to live, and I want to do it in the most fulfilled and meaningful way possible—that’s the best outcome for me, and I do a lot more good for the world that way. Wisdom gives people the insight to know what “fulfilled and meaningful” actually means and the courage to make the choices that will get them there.

And while life experience can contribute to wisdom, I think wisdom is mostly already in all of our heads—it’s everything the Higher Being knows. When we’re not wise, it’s because we don’t have access to the Higher Being’s wisdom because it’s buried in fog. The fog is anti-wisdom, and when you move up the staircase into a clearer place, wisdom is simply a by-product of that increased consciousness.

One thing I learned at some point is that growing old or growing tall is not the same as growing up. Being a grownup is about your level of wisdom and the size of your mind’s scope—and it turns out that it doesn’t especially correlate with age. After a certain age, growing up is about overcoming your fog, and that’s about the person, not the age. I know some supremely wise older people, but there are also a lot of people my age who seem much wiser than their parents about a lot of things. Someone on a growth path whose fog thins as they age will become wiser with age, but I find the reverse happens with people who don’t actively grow—the fog hardens around them and they actually become even less conscious, and even more certain about everything, with age.

When I think about people I know, I realize that my level of respect and admiration for a person is almost entirely in line with how wise and conscious a person I think they are. The people I hold in the highest regard are the grownups in my life—and their ages completely vary.

Another Look at Religion in Light of this Framework:

This discussion helps clarify my issues with traditional organized religion. There are plenty of good people, good ideas, good values, and good wisdom in the religious world, but to me that seems like something happening in spite of religion and not because of it. Using religion for growth requires an innovative take on things, since at a fundamental level, most religions seem to treat people like children instead of pushing them to grow. Many of today’s religions play to people’s fog with “believe in this or else…” fear-mongering and books that are often a rallying cry for ‘us vs. them’ divisiveness. They tell people to look to ancient scripture for answers instead of the depths of the mind, and their stubborn certainty when it comes to right and wrong often leaves them at the back of the pack when it comes to the evolution of social issues. Their certainty when it comes to history ends up actively pushing their followers away from truth—as evidenced by the 42% of Americans who have been deprived of knowing the truth about evolution. (An even worse staircase criminal is the loathsome world of American politics, with a culture that lives on Step 1 and where politicians appeal directly to people’s animals, deliberately avoiding anything on Steps 2-4.)

So What Am I?

Yes, I’m an atheist, but atheism isn’t a growth model any more than “I don’t like rollerblading” is a workout strategy.

So I’m making up a term for what I am—I’m a Truthist. In my framework, truth is what I’m always looking for, truth is what I worship, and learning to see truth more easily and more often is what leads to growth.

In Truthism, the goal is to grow wiser over time, and wisdom falls into your lap whenever you’re conscious enough to see the truth about people, situations, the world, or the universe. The fog is what stands in your way, making you unconscious, delusional, and small-minded, so the key day-to-day growth strategy is staying cognizant of the fog and training your mind to try to see the full truth in any situation.

Over time, you want your [Time on Step 2] / [Time on Step 1] ratio to go up a little bit each year, and you want to get better and better at inducing Step 3 Whoa moments and reminding yourself of the Step 4 purple blob. If you do those things, I think you’re evolving in the best possible way, and it will have profound effects on all aspects of your life.

That’s it. That’s Truthism.

Am I a good Truthist? I’m okay. Better than I used to be with a long way to go. But defining this framework will help—I’ll know where to put my focus, what to be wary of, and how to evaluate my progress, which will help me make sure I’m actually improving and lead to quicker growth.

To help keep me on mission, I made a Truthism logo:

That’s my symbol, my mantra, my WWJD—it’s the thing I can look at when something good or bad happens, when a big decision is at hand, or on a normal day as a reminder to stay aware of the fog and keep my eye on the big picture.

And What Are You?

My challenge to you is to decide on a term for yourself that accurately sums up your growth framework.

If Christianity is your thing and it’s genuinely helping you grow, that word can be Christian. Maybe you already have your own clear, well-defined advancement strategy and you just need a name for it. Maybe Truthism hit home for you, resembles the way you already think, and you want to try being a Truthist with me.

Or maybe you have no idea what your growth framework is, or what you’re using isn’t working. If either A) you don’t feel like you’ve evolved in a meaningful way in the past couple years, or B) you aren’t able to corroborate your values and philosophies with actual reasoning that matters to you, then you need to find a new framework.

To do this, just ask yourself the same questions I asked myself: What’s the goal that you want to evolve towards (and why is that the goal), what does the path look like that gets you there, what’s in your way, and how do you overcome those obstacles? What are your practices on a day-to-day level, and what should your progress look like year-to-year? Most importantly, how do you stay strong and maintain the practice for years and years, not four days? After you’ve thought that through, name the framework and make a symbol or mantra. (Then share your strategy in the comments or email me about it, because articulating it helps clarify it in your head, and because it’s useful and interesting for others to hear about your framework.)

I hope I’ve convinced you how important this is. Don’t wait until your deathbed to figure out what life is all about.

Related Wait But Why Posts

Life is a Picture, But You Live in a Pixel

What Makes You You?

Taming the Mammoth: Why You Should Stop Caring What Other People Think

-

Unrelatedly, after finishing my outline for this post, I estimated that the writing part would take me 10 hours—which is odd, because I’m about eight hours in now and still on Step 1 of the staircase. You’d think that after writing about 50 posts in the past year and underestimating how long each of them would take, I might not have been so dramatically delusional by this point. You’d think.

If you were to continue thinking, you might also assume that yesterday, when I needed to go from 116th Street in Manhattan to the World Trade Center for an event I absolutely could not be late for, I’d have considered the fact that I know from experience that this usually takes an hour before leaving for the event only 40 minutes ahead of time. We agree that that’s what you’d think. So why was I sprinting at the end to make it there on time? Why would I end up sweating to make it somewhere on time—for the nine trillionth time in my life—when this grossly undignified and unpleasant experience is so easily avoidable?

Because when I make these inexplicably stupid, self-defeating decisions, I’m swimming in fog.↩

I use a weird one, where I pretend I have a dial I can set to a number of sleep hours and then press the button and instantly it’s that many hours later and I’ve slept the number of hours on the dial, and I can resume doing what I’m doing. I’m a night owl, but if I had that dial, I’d go to bed around 11pm and sleep eight hours almost every night of the year. This isolates for me the fact that I’m not actually a night owl—my Higher Being wants to sleep from 11-7—it’s just that I have a short-sighted, fog-based resistance against going to sleep. Which probably annoyingly boils down to fear of death somehow.↩

Sidenote: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQr8UWuVefA↩

Some dispute that Kelvin said this, claiming it was actually said by another great 19th century physicist, Albert A. Michaelson. Whichever account is correct, a great scientist said it.↩

This theory went out of style with the popularity of inflationary theory, but some prominent physicists are now questioning the validity of inflationary theory.↩

The post A Religion for the Nonreligious appeared first on Wait But Why.